You've heard of this material called acetate.

But what the heck is cellulose and what's it got to do with spectacle making?

We've delved into a little material science for you to help explain what this material is and why it's so good for making high-quality glasses.

Acetate glasses are made from a bioplastic called cellulose acetate. This material is a natural compound which derives from the fibres in cotton 'bolls' or wood pulp.

Due to their high levels of cellulose, wood or cotton are both excellent sources which are cultivated, refined and mixed with acetic acid to make the sheet material, cellulose acetate.

Let's look into where acetate is made and why it's our favourite material for making our handmade spectacles and sunglasses.

What is acetate?

Today, we’re getting a bit biological.

Technical perhaps...

But simply putting it, you should think of cellulose as nature’s building-block.

It makes the main structural component found within the cell-walls of many types of plant, algae, tree and bacteria.

"Cellulose is the most common organic compound on Earth. About 33% of all plant matter is cellulose."

Interestingly, different types of fauna contain varying levels of cellulose.

To make sheet acetate, the main source of the cellulose is taken from the white ‘bolls’ of cotton plants or wood pulp as they have very high cellulose purities of as much as 90%.

|

Source |

Cellulose % (avg) |

|

Cotton |

90% |

|

Hemp |

57% |

|

Wood |

50% |

|

Coconut |

40% |

|

Flax |

33% |

|

Sisal |

33% |

Cellulose from cotton or wood pulp is taken and refined into purified cellulose.

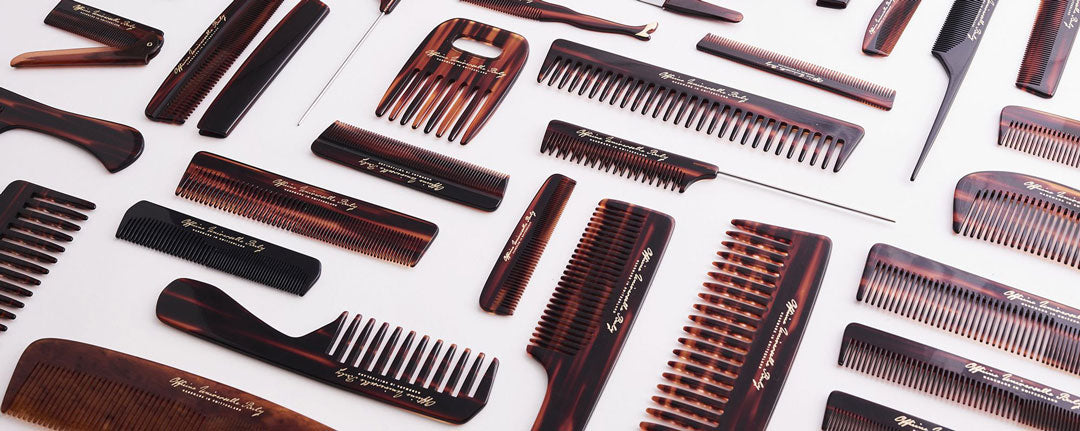

This extraction is used to make the acetate compound for the manufacture of sheet acetate, used to make spectacles, sunglasses and other items such as hair combs.

To see how this all works, check out the video below to how the compound is processed, dyed and formed by Italy’s oldest and most revered acetate manufacturer; Mazzucchelli.

How is cellulose acetate made?

Is cellulose acetate natural?

Absolutely. It grows.

To make acetate sheets for the production of eyewear, the lifecycle of the cotton begins in vast cotton crops. Usually in the regions of America, Africa and Asia

Commercial harvesting is carried out via machine which only removes the characterising white ‘bolls’ from the top of the plants, keeping the rest intact.

Once collected, the cotton is then decontaminated from field-debris and insects before being refined into purified cellulose.

1. From the field...

2. To the factory

In a process called organic synthesis, the purified cellulose is mixed with acetic acid.

This formula induces the creation of the compound we know as cellulose acetate.

At this stage, the acetate compound is a neutral, semi-opaque mixture with a very thick viscosity similar to putty or playdough.

3. Adding colour

Using what is called disperse dye, various colours can be introduced to the neutral acetate compound.

For the production of acetate, the disperse dyes are in powdered form which can be pre-mixed to make bespoke colours.

For large batches, the dyes are thoroughly mixed through the acetate by repeatedly rolling the compound through flat metal rollers. This is carried out by skilled workers which you can see in this video.

For small or development batches, the dyes can be manually incorporated by hand. Much like a pastry mix, it’s kneaded, squashed and rolled to achieve a consistent colour throughout the soft compound.

See the images below, courtesy of Mazzucchelli.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Dispersing dyes

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Mixture of red & black dispersing dye

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Incorporating the dyes.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Hand mixing the dyes.

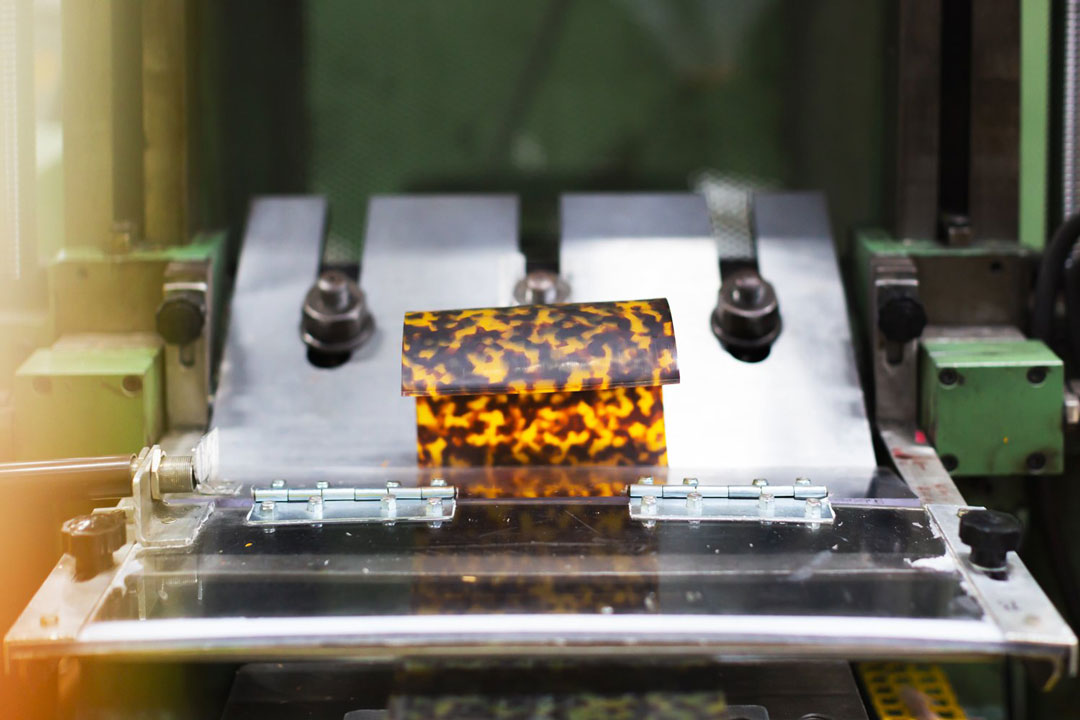

4. Block casting

Once thoroughly mixed and rolled, the dyed acetate compound is then placed into large box-shaped moulds.

This is the process known as casting which produces ‘block acetate’ where the compound is cured* as very large blocks before cutting. (Italy’s signature method of acetate production.)

For large batches the acetate is cast inside large 2 metre long block-moulds which are hydraulically squeezed under pressure. This removes any air bubbles and forces patterned acetates with alternating chips/slices to adhere together.

For small batches the process is identical except from the size of the block-moulds. Seen in the images below, manual whell-presses are uses to exert the necssary pressure to form the acetate blocks.

* Curing: In the production of plastics, curing, is the process of toughening or hardening a polymer where it changes state to become more solidified.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Hydraulic wheel press (open)

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Hydraulic wheel press (closed)

5. Patterns & tones

Once cured, the acetate is ready to be sliced into finished sheets or ‘chipped’ into tiny coloured pellets.

Sounds strange, but the reason for chipping, is that the pellets can be heated and interspersed with other colours of acetate.

By artfully layering differing tones, opacity's and colours of pre-made acetate, the chips are placed back into the moulds to make a hybrid block of speckled acetate such as imitation tortoise shell.

It's these extensive and lustrous acetate patterns which have made Italian acetate so desirable within the optics industry.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Chipped acetate.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Amber & black chips.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Cured acetate block.

6. Slicing sheets

Once fully cured, the acetate blocks are placed onto a moving bed which hydraulically pushes the block against an angled cutting knife.

Much like a wood-pane, the knife is set at a pre-determined sheet thickness which shaves layers off the acetate block into sheets of acetate.

Seen in the images below, the freshly cured sheets are still malleable and bendy. Because of this, they tend to curl-up as they're being cut from the block.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Small sheet slicing.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Large sheet slicing.

7. Stabilisation

The sheets are manually removed by skilled workers who hang the sheets of freshly cut acetate in what look like coat-rails, ready for heat-stabilisation.

In an oven, the acetate is held at a consistent temperature for several days before storage or dispatch, ready for glasses making here in our workshop in Scotland.

It’s a fine art.

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Acetate sheets hanging

Image credit: Mazzucchelli 1849 Spa. | Acetate sheets hanging

Making acetate glasses frames

Two things you should know.

Sheet acetate for glasses is made in various countries around the world.

Whilst there are many factories that do this, ours comes from Europe’s oldest and best producer in Northern Italy. Not only are they experienced. They’re also the closest to us here in Glasgow.

Which is nice, considering we can reduce the carbon footprint shipping with a material that can biodegrade

So once every month or so, large sheets of freshly made acetate arrive outside our workshop doors.

Large and bendy, we cut them into more manageable strips using a table saw and two pairs of steady hands.

Our hands.

What are acetate glasses?

Since the 1940’s, cellulose acetate has been marketed using various trade-names.

Depending on the manufacturer and location, it can be referred to as Zylonite, Zylo, Zyl, Cellon, Celluloid, Tenite or Rhodoid.

But regardless of name, the material itself was always made using cellulose, deriving from wood pulp or cotton bolls.

In basic form, there are three main parts of glasses frames.

- An acetate frame-front

- Two acetate sides (otherwise known as temples.)

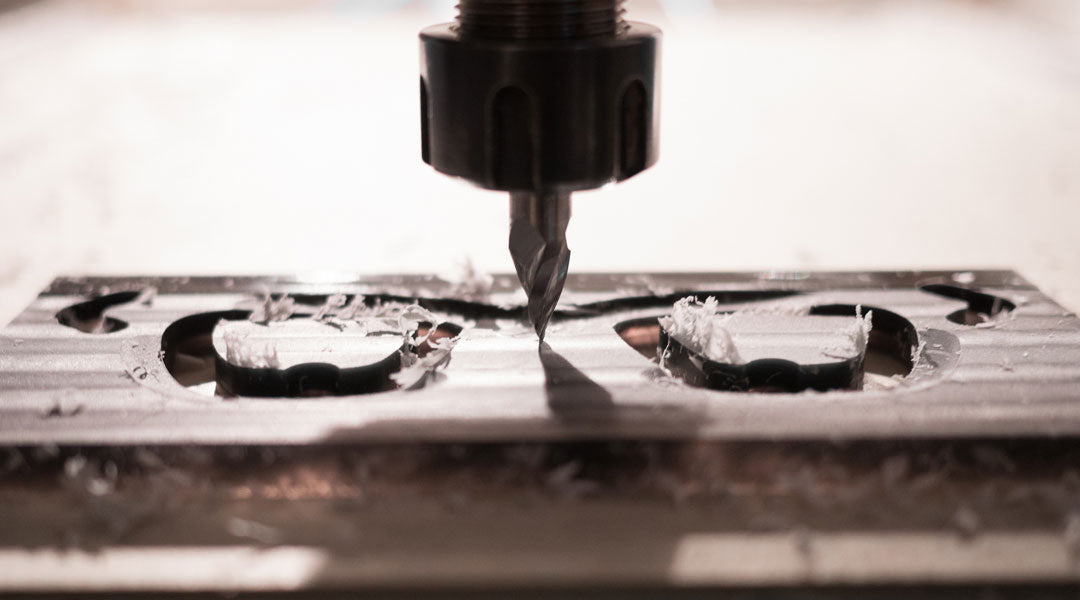

Frame front

Frame fronts are generally a 6/8mm thick section acetate that is machined using precision CNC milling.

Using various cutting bits, the frame front is sculpted at various angles, speeds and RPM (revolutions per minute.)

Lens holes, lens grooves, hinge graves, hinge holes and nose apertures are all cut from a single piece of acetate to make the front.

After machining, following stages of heating and forming take place to give the frame it's curvature to accept lenses and for facial comfort.

Temples

Sometimes they're called legs or arms.

You can see why... but the proper name is temples.

Similar to the frame front, they're CNC machined or die-cut from a thinner 4/6mm thick acetate.

To maintain their shape and curvature, acetate temples are usually reinforced by a metal ‘core’. This is achieved by heating the temple and quickly forcing a pointed core into the heated acetate temple.

The process is known as wire shooting.

The cores can often be commonly seen within the temple, especially if the acetate is transparent providing nice detail, quality and longevity.

What are the benefits of acetate for glasses?

Sheet acetate has a number of benefits which makes it perfect for spectacle making.

As mentioned previously, acetate is a bio plastic which supersedes synthetic alternatives due to the fact it can biodegrade.

Other major benefits include…

- Hypoallergenic | which means it won’t react with your skin. [?]

- Lightweight | making it easy to wear for long periods of time without sliding down your nose or becoming cumbersome or uncomfortable.

- Vast colour options | due to the way it can be dyed during the manufacture process. This yields endless colour and pattern options to suit many different styles and skin tones.

- Can be transparent | which other materials cannot achieve.

- Made from natural fibres | Whilst cotton grows, it absorbs C02 emissions and creates jobs via cultivation, harvesting and processing. Synthetic fibres and compounds use more energy to produce and have a higher carbon footprint in their production.

- Adjustable | With experience, opticians and frame makers like us have the ability to heat and manually adjust acetate glasses frames. In turn, they’re more comfortable for you to wear. [?]

Other glasses making materials.

Prior to acetate, glasses frames were made using natural materials.

As early as the 13th century, substrates such as real tortoise shell, animal bone, ivory, wood and leather were all used to hold glass lenses in rudimentary spectacle frames.

Obviously, taboo materials like ivory and tortoise shell are no longer used for spectacle making. Substrates such as these have since been banned by various countries under various trading laws.

And frankly, the superior properties of acetate make these unsustainable and unethical materials comparably inferior.

Recently, for niche optical brands, wood is still a viable material thanks to it’s eco-friendly, lightweight properties. It's a tricky material to make suitably thin for glasses, but reinforcing metal and resins can help with durability.

"When we began making glasses frames, we used to make our prototype frames from wood.

Because if you can make frames from wood, you can make them from pretty much anything."

Where is cellulose acetate made?

Today, the acetate used for glasses making is predominantly produced in Italy or Japan.

Increasingly, acetate production has also emerged in China however this is a growing industry which is yet to meet the same levels of quality by their European or Asian peers.

Depending on the supplier, these manufacturers produce various types of acetate which have their own set of colours, patterns and characteristics.

Italian acetate is renowned for it’s colouration and pattern variability.

This is due to their preferred method of casting which produces what is known as ‘block-acetate.’ This method tends to yield a generally softer acetate which lends itself towards thicker, full-rim acetate glasses frames.

Japanese acetate, also known as Takiron is known for being more rigid and harder in terms of density.

This is due to the way the acetate is extruded through dies under very high pressure. Japanese spectacles and sunglasses made from Takiron can be made slightly thinner and are less likely to deform due to the heightened rigidity of the acetate.

What else is cellulose acetate used for?

After the second world war, the polymer technology began to rapidly advance.

This was due to a spike of wartime production methods and lack of accessibility to natural materials.

Traditional materials such as bone, ivory, wood and leather were quickly eclipsed by the emerging polymer industry during the 1940’s.

Cellulose acetate was introduced across various sectors, both in textiles and as a hard-edged products.

Textiles

- Blouses

- Shirts

- Trousers

- Curtains

- Absorbent medical dressings

- Cigarette filters

Hard Products

- Spectacles

- Tool handles

- Hair Combs

- Photographic film

- Playing cards

- The original Lego bricks

Does cellulose acetate biodegrade?

Found wirthin plants and trees, cellulose can of course biodegrade.

Made into acetate, it still retains this biodegradability, albeit at a slower rate of decomposition.

When acetate was originally conceived in 1865, it was considered that acetate would have very poor biodegradability.

However, during tests by Springer-US shows that acetate can decompose in moist soils.

“Several studies have confirmed that CA is indeed biodegraded in a natural environment as measured by a variety of methods.”

Puls, J, Wilson, S.A. & Hölter, D. J Polym Environ (2011) 19: 152.

How long does it take for cellulose acetate to decompose?

Tests were carried out in 1997 via ResearchGate, where a cellulose acetate cup was left in waste sewage for a period of 18 months.

During which time, the cup lost 70% of it’s original weight.

Whilst it didn’t fully disappear within the 18-month period, a 70% mass reduction is a promising rate of degradation.